What you should know about drill cuttings

I believe drill cuttings are an excellent data source that is often overlooked despite being widely available. Drill cutting samples are your most continuous source of physical rock data before and after drilling. In some cases the only other source of such continuous physical information would be an outcrop, but these aren't always located in close proximity to your area of interest.

There is a general distrust of drill cuttings in today's geoscience world due to the nature of their collection and the imprecise data they provide. In this article I hope to highlight some of the issues and benefits of drill cuttings so that you might be more inclined to use them in the future. We will cover the most common aspects of sample collection, mitigating incorrect data, and why quantity over quality matters.

Sample Collection

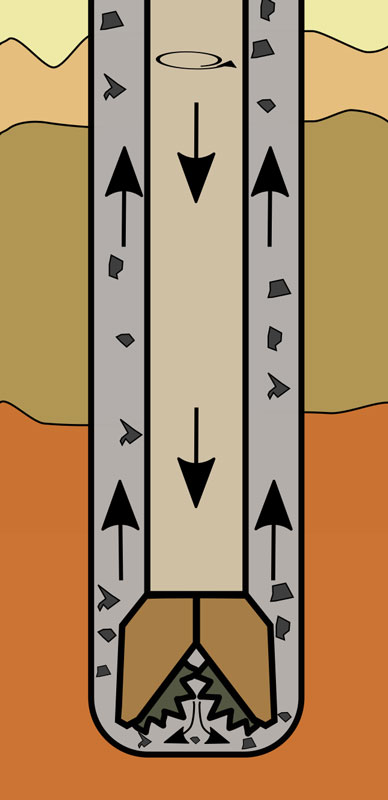

As a drill bit penetrates the earth, drilling fluid is pumped through the end of it. In addition to reducing friction and wear on the bit, the fluid also carries drill cuttings back up the wellbore to the surface, where the drilling mud and cuttings are passed over a shale shaker that separates the cuttings from the fluid. At the end of the shaker, samples of the cuttings are collected for analysis. By examining the cuttings, the wellsite geologist is able to determine what rock types and formations the well bore is passing through.

As you can imagine, there are several points where the sample can become contaminated with other drilling materials from previous intervals or from material where the well bore has partially caved in.

Despite this, however, a majority of samples are still representative and by correlating with gamma, neutron, sonic and other MWD or wireline measurements, it is possible to accurately inform drilling engineers and others as to what exactly is going on at the well bore.

Ways to mitigate incorrect data

Knowing all of the ways that data could be contaminated can allow us to mitigate these risks to ensure good analysis and that proper drilling decisions are being made.

Here are some key things to keep in mind:

Proper collection of cuttings is critical. If you're using a pail, the sample catcher must be shown how to properly grab a representative sample. The pail should be placed off center at the end of the shaker and held in place by a rope. When the sample is collected from the pail it must be grabbed from several locations within the pail. The sample catcher should grab a handful of samples from the top, middle and bottom of what was collected in the pail thus ensuring a more representative sample.

More advanced catching technologies are now available, however they are not widely used yet. I have personally used Sample Pro LTD's product which sits on the end of a shale shaker and catches a very representative sample.

If you are relying on strip logs that have already been created for your company or that are publically available, it's important to consider several factors when assessing the quality of a pre-made strip log:

- What type of mud was used? This is important because oil based muds make hydrocarbon identification through fluorescence impossible. Very thick oil mud may even stain the sample and give a false visual. Water based muds tend to have more wellbore cavings in the samples.

- What speed was the well drilled at? This factor generally applies to more recent wells, it is important to note that drilling has become so fast that it can be difficult for sample catchers keep up or for wellsite geologists to provide detailed descriptions of each sample.

- What type of bit was used? PDC bits tend to produce much finer cuttings and fragments which makes for an inferior sample, particularly through fine unconsolidated sands. Tricone bits tend to provide a much better sample but drill slower. Sample quality will directly affect the quality of the strip log.

- Was the strip log created during or after drilling? Strip logs made on wellsite will lack the detail of one created post drilling in a lab environment, depending on speed. Post well creation has added benefit of wireline logs for control if available for accurate top identification.

- Do the MWD or wireline logs match the lithology? Question strange readings or lithology interpretations that don't match, as the sample may have been poorly captured or poorly described.

Many wellsite geologists are excellent at what they do and successfully steer wells based on what they see in the cuttings, but many just don't have the time to systematically analyze every sample to its fullest. That is why Canstrat developed a method which helps to remove bias and missing data, but one should always take the time to compare a strip log to the original data source if it's available.

Tricone vs PDC bit

If the drill cuttings have already been collected, the best way to improve your cuttings data is to recognize what doesn't belong and concentrate on the valid information from that interval. You will want to analyze the representative rock using a methodology that is repeatable for every sample and allows you to capture all the present information. The Canstrat Method is one such system and produces excellent sample descriptions.

Before analyzing the drilling cuttings you should become familiar with what lithologies to expect in that interval or formation. Reference whatever material you can from WSCB Atlas, strip logs, or web-based references such as Wikipedia. This will allow you to identify cuttings that may not belong or ones that need further analysis.

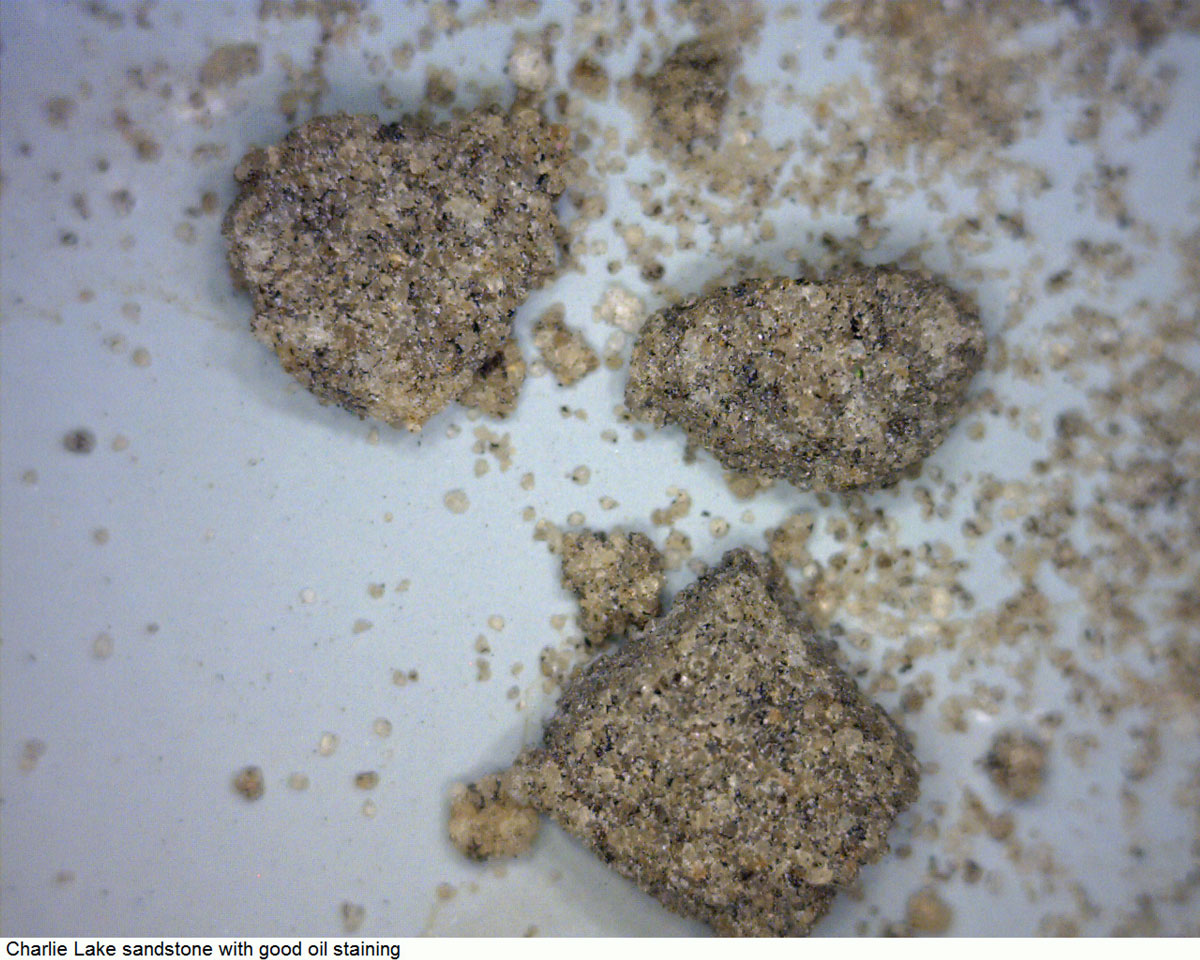

The next step is to access core if available and calibrate your eye to recognize what part of the sample is actually from that interval. This will allow you to see the rock as a whole piece and teach you what texture and structures may be present but hard to see in cuttings. Become very familiar with how the rock looks under the microscope at different magnifications both dry and wet. Once you have identified the rock type learn the main textures, compositions, and structural features your interval contains. Now you will be able to go back to the cuttings and easily recognize what doesn't belong.

Learning to identify cavings is a big part of sample analysis. Cavings are bits of rock that fall in from the well bore after the bit had drilled that section. They tend to be larger than actual drill cuttings which have been ground down by bit action. Cuttings generally range in size from 1/8' to 5/8' with cavings being larger. Cavings can also look out of place in terms of lithology. If you see some dark shales present in an interval that is known for brown shales they may be cavings, for example.

Finally you will need to be able to identify Lost Circulation Material, or LCM, which is material that is used to help plug up porous intervals to prevent mud loss. These materials can be a variety of substances including plastic, rubber, walnuts and calcium carbonate.

If you want to learn more about cavings and LCM, you can download Canstrat's Caving and Foreign Materials guide here.

Please note: this download requires a valid email address.

Quantity over Quality

Using drill cuttings is a choice of quantity over quality. It is highly unlikely that you will ever get a perfect representative sample, but drill cuttings provide you with an abundance of representation and availability.

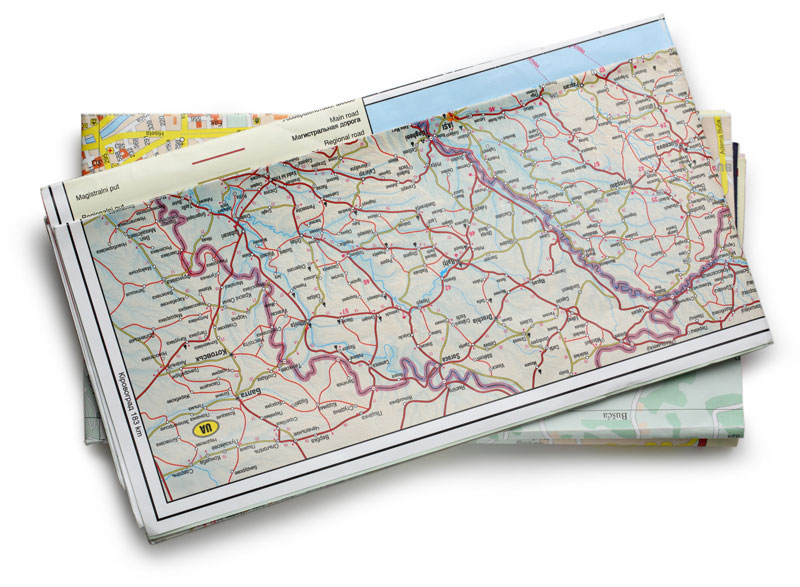

A good analogy for drill cuttings is to think of a road map and imagine what the world was like before Google Maps. If you were on a road trip you used a paper road map. This map showed you major roads, landmarks, cities, and gave you a general idea of where you were based what you encountered. Drill cuttings analysis is similar to that road map; the well bore is your highway, the formation tops are your cities and the geological markers are landmarks. This all provides you with a fairly accurate idea of where you are in the subsurface especially if correlated to other available data.

Core is the best quality of rock data that can be extracted from the subsurface, but its relative scarcity is also important to keep in mind. If you have only 1 interval of core for an area that is several sections, you are relying on a very small piece of information to tell you how an interval is behaving over a very large area. The abundance of drill cuttings however allows you to expand your view of the subsurface by providing you with more rock data that can be correlated back to core. Correlating with other available data such as wireline logs and seismic enables you to see a much clearer picture of the subsurface.

In Canada, most provinces require a copy of the samples to be sent to a regulatory board to be stored at a sample depot. In the WCSB there is a good bet drill cuttings can be found near your area of interest. In the United States they can be a little harder to find depending on your States regulations. A vast majority of Canstrat's American strip logs cuttings have been donated to the Denver Core Research Center under the Amstrat Collection.

Seeing the forest for the trees

"Can't see the forest for the trees" is a good idiom when thinking about cuttings and geology in general. It is important not to be so absorbed in small detail that you miss the larger picture. Cuttings are not a perfect data source but you shouldn't discredit their value based on the recognized pitfalls associated with them. While cuttings should not be the only lithology data you use, their availability over the entirety of the wellbore make them a valuable tool for representing the subsurface. Cuttings give you the power to see the small and big picture using actual rock data.

If you would like to learn more about drill cuttings, check out our course page to get hands on experience with hundreds of real world samples.

Also, sign up for our monthly newsletter which provides resources and articles on drill cuttings.